You are here: » Christianity in View » Introduction to the Orthodox Church » About Orthodoxy

What is ‘Orthodoxy’ ?

What is ‘Orthodoxy’ ?

The word derives from two Greek words: Orthos meaning ‘Right’ and Doxa meaning ‘Belief’ or ‘Worship’. Thus Orthodoxy refers to the practice of the right belief and worship. The Orthodox Church of today claims to be identical with the undivided church of the past.

The Orthodox Church is evangelical, but not Protestant. It is orthodox, but not Jewish. It is catholic, but not Roman. It isn’t non-denominational – it is pre-denominational. It has believed, taught, preserved, defended and died for the Faith of the Apostles since the Day of Pentecost 2000 years ago.

Quotation courtesy of Religious Tolerance.org

Organisation of the Orthodox Church

Organisation of the Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox church is composed of a family of churches, each in communion with each other and sharing a common set of beliefs, but unlike the Roman Catholic Papacy, there is no supreme head over all of them. Although each church shares the beliefs of the others, there are variations in custom and practice within each jurisdiction. The Eastern Orthodox churches may be divided into two groups:

- Autocephalous (‘self-headed’) churches. These elect their own bishops and are totally self-governing. Examples are the churches of Antioch (Now known as Antakya, in Turkey), Greece and Russia. There is also the Church of Constantinople, sometimes referred to as the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Bishop of this church has the status of First among equals, that is a position of honour amongst all other bishops in the Orthodox church. This position dates back to the ecumenical council held at Constantinople in 381, at which was declared: “The Bishop of Constantinople shall have the primacy of honour after the Bishop of Rome, because it is New Rome.”

- Autonomous (‘self-ruling’) churches. These cannot appoint their own bishops but have them confirmed by an Autocephalous church. In all other respects, they have complete self-government.

The Oriental Orthodox church likewise is composed of six autocephalous churches – the Coptic, Ethiopian, Eritrean, Syriac, Armenian and Indian (Malankara) churches.

Eastern Orthodox Church Diagram

Eastern Orthodox Church Diagram

Oriental Orthodox Church Diagram

Oriental Orthodox Church Diagram

History of the Orthodox Church

History of the Orthodox Church

Up to the time of the Council of Chalcedon in 451, East and West formed one church. The council chose to affirm that there were two natures in Christ;one human, the other divine. Both natures were united in a single hypostasis or person*. This view was rejected by several churches who believed in a single nature in Christ. These churches are called Oriental Orthodox or Non-Chalcedonian to distinguish them from the Eastern Orthodox churches. They are found mainly in the following countries:

- Armenia

- Egypt (‘Coptic’ churches)

- Ethopia and Eritrea

- Syria

* This is sometimes called the ‘Chalcedonian Definition’ with the full text available on the Creeds of Christianity page.

Due to their belief in the one nature, the Oriental Orthodox churches were labelled ‘Monophysite’ (physis is the Greek term used for ‘nature’). The label is disavowed by Oriental Orthodox Christians, who prefer the term ‘Miaphysite’. In the writings of Cyril of Alexandria (376-444), mention is made of the one nature of Christ, as the incarnate God, together with a union of natures. Miaphysitism argues that Christ as the word of God incarnate has a single nature, containing both human and divine elements, and united without any degree of separation or change.

Both Eastern and Oriental Orthodox have met on several occasions to provide a framework toward eventual reunion. The last such meeting was held in Geneva in 1993.

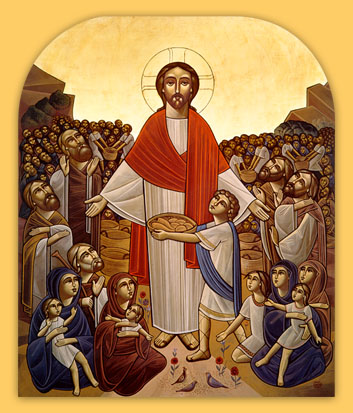

Coptic Orthodox Icon of Christ Feeding the Multitude

NOTE: Generally, from now on, this website will use the term ‘Orthodox’ to refer to the Eastern Orthodox churches only.

After the separation of the Oriental Orthodox churches, East and West gradually drew apart. Some of the reasons for this included:

- The claims of the Pope*, as Bishop of Rome, to be the supreme head over the church.

- Differences in language and culture – Latin was widely used in the west, Greek in the east.

- Liturgical differences such as the use of bread that was leavened (East) or unleavened (West) in the Eucharist.

* The head of the Coptic church in Egypt and the Eastern Orthodox Patriarch of Alexandria & all Africa are also styled with the title ‘Pope’.

A significant disagreement between Rome and Constantinople took place in 858, with the appointment of Photius (c. 820-891) as Patriarch of Constantinople. His successor (Ignatius I) had been deposed by the eastern emperor Michael III (839-867), but Ignatius refused to step aside and his case was taken up by Pope Nicholas I (c. 820-867). Photius found himself excommunicated by the Pope in 867 and he replied in kind. The dispute was not settled until Ignatius died in 878.

However, perhaps the major cause of estrangement was the addition of the so-called Filioque clause (Latin: ‘and the son’) to the Nicene creed. Part of the creed would thus read:

Et in Spiritum Sanctum, Dominum, et vivificantem: qui ex Patre Filioque procedit.

..and in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life, who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

The West inserted this into the creed at a provincial church council in Toledo, Spain in 589. Ostensibly this was done to protect against the Arian heresy, which denied that Christ was co-eternal and co-equal with the father, but was simply a created being. The Orthodox churches objected to the addition arguing that firstly, the addition was done outside of an ecumenical council and so could not be accepted by the whole church, and secondly (and more importantly), the addition implied that there were two sources of deity in the one Godhead. In 1014, the Filioque was officially accepted in Rome.

The separation became more intense until in 1054, Pope Leo IX and the Patriarch of Constantinople, (Michael I) both excommunicated each other. Their respective churches now claimed the title of the ‘One true church’. In 1204 the Crusading armies looted Constantinople and in doing so, reinforced the separation.

Essay on the East-West schism

Essay on the East-West schism

Attempts were made in 1274 and 1439 to reunify East and West, but both attempts failed due to lack of support from the East. In 1453, Constantinople finally fell to the invading Ottoman armies, striking a decisive blow against the unity of Christendom.

A Mosaic from the Hagia Sophia

(The former Church of the Holy Wisdom in Constantinople, now known as Istanbul).

In 1965, both sides agreed to lift the mutual anathemas on each other. As a sign of greater understanding and reconciliation, several Orthodox Bishops attended the funeral of Pope John Paul II in April 2005. The following year, John Paul’s successor (Benedict XVI) met the ecumenical patriarch (Bartholomew I) in a historic meeting in Turkey. The warmth and friendliness of the meeting resulted in a joint declaration. The extract below indicates the commitment of both churches to work together for unity:

“…As far as relations between the Church of Rome and the Church of Constantinople are concerned, we cannot fail to recall the solemn ecclesial act effacing the memory of the ancient anathemas which for centuries had a negative effect on our Churches. We have not yet drawn from this act all the positive consequences which can flow from it in our progress towards full unity, to which the mixed Commission is called to make an important contribution. We exhort our faithful to take an active part in this process, through prayer and through significant gestures….“

With regard to the ecumenical movement within Christianity, the Orthodox church is a member of the World Council of Churches, which also contains most of the main Protestant denominations.

List of Orthodox Churches in communion (including autonomous churches and exarchates)

List of Orthodox Churches in communion (including autonomous churches and exarchates)

NOTE: The order of ranking for Bishops in the Orthodox churches is as follows:

1. Patriarch, 2. Exarch, 3. Metropolitan.

Eastern Orthodoxy

Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople

- Autonomous Orthodox Church of Finland

- Autonomous Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church (Autonomy not recognized by the Church of Russia)

- Self-governing Orthodox Church of Crete

- Self-governing Monastic Community of Mount Athos

- Exarchate of Patmos

- Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain

- Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Italy and Malta

- Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

- Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia

- Exarchate of the Philippines

- Patriarchal Exarchate for Orthodox Parishes of Russian Tradition in Western Europe

Orthodox Church of Alexandria

Orthodox Church of Antioch

- Self-governing Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America

Orthodox Church of Jerusalem

- Autonomous Church of Mount Sinai

Orthodox Church of Russia

- Autonomous Orthodox Church of Japan

- Autonomous Orthodox Church of Ukraine

- Self-governing Orthodox Church of Moldova

- Self-governing Orthodox Church of Latvia

- Self-governing Estonian Orthodox Church (Autonomy not recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate)

- Self-governing Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia

- Exarchate of Belarus

Orthodox Church of Georgia

Orthodox Church of Serbia

- Autonomous Archdiocese of Ohrid

Orthodox Church of Romania

- Self-governing Metropolis of Bessarabia (Autonomy not recognized by the Church of Russia)

Orthodox Church of Bulgaria

Orthodox Church of Cyprus

Orthodox Church of Greece

Orthodox Church of Poland

Orthodox Church of Albania

Orthodox Church of the Czech lands and Slovakia

Orthodox Church in America (Became Autocephalous in 1970 from the Russian Orthodox Church).

Estonian Apostolic Orthodox Church (Autonomy recognized only by the Ecumenical Patriarchate)

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Armenian Apostolic Church

- The Holy See of Cilicia

- The Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople

- The Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem

The Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria

- The British Orthodox Church in the United Kingdom

- The French Coptic Orthodox Church in France

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church

The Indian (Malankara) Orthodox Syrian Church

The Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch (also known as the Syrian Orthodox Church of Antioch)

- The Malankara Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church

Bartholomew I and Pope Benedict XVI in Turkey, 2006.

Photo by N. Manginas

© Ecumenical Patriarchate, 2006.

Orthodox belief and practice

Orthodox belief and practice

As we have noted, the Orthodox church claims to be the one true church, with an unbroken lineage stretching back to the first apostles. We shall consider Orthodox belief and practice under the following headings:

- Common beliefs with all Christians

- Common beliefs with Roman Catholics

- Orthodox Distinctives

NOTE: An Orthodox view of Protestantism is given in the Orthodox Q and A section.

Common Beliefs with all Christians

Common Beliefs with all Christians

The Orthodox church affirms that there is one God, in three distinct persons. As with other Christians, the Nicene Creed is used as a profession of faith. The only difference being, as we noted above, that the Holy Spirit is said to proceed from the Father alone.

The Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.

We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven:

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary,

and was made man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.

We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father.

With the Father and the Son he is worshipped and glorified.

He has spoken through the Prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come.

A Russian icon depicting the council at Nicea (325).

Common Beliefs with Roman Catholics

Common Beliefs with Roman Catholics

As in the Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church accepts the idea of Apostolic succession, i.e. the idea that the bishops follow an unbroken line of succession from the Apostles. Doctrinal authority resides in Tradition (capital ‘T’): The Bible, church councils and creeds etc. The writings of the church fathers are also considered important. This Tradition (Greek: paradosis) is distinguished from ‘tradition’, which includes local and national customs. Orthodoxy believes that the Holy spirit acts to guide the church into the truth.

Biblically, there are a number of additional books (which are known as deuterocanonical (Greek: ‘Second Canon’) in use in Orthodox Bibles and Roman Catholic Bibles, alongside the normal canon of 66 books of scripture as used by Protestants.

These are:

1 Esdras, 2 Esdras, Tobit, Judith, Additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Baruch with the Letter of Jeremiah, Song of the Three Young Men and Prayer of Azariah, Story of Susanna, Bel and the Dragon, Prayer of Manasseh, 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees.

In addition, the following books are found in Orthodox Bibles only:

3 Maccabees, Psalm 151.

There are seven Sacraments (known as ‘Mysteries’ in Orthodoxy). These are: Baptism, Chrismation*, Eucharist, Holy Orders, Penance, Anointing of the sick and Holy Matrimony.

* Known as Confirmation in the West.

As in the Catholic church, the Saints are venerated and special attention is paid to Mary, who is often called the Theotokos (Greek: ‘God-bearer’). However, Orthodoxy does not accept the Catholic view that Mary was immaculately conceived. An overview of the Orthodox view of Mariology is found in the Q and A section.

“It is truly meet to bless you, O Theotokos, ever blessed and most pure, and the Mother of our God. More honorable than the cherubim, beyond compare more glorious than the seraphim, without corruption you gave birth to God, the Word. True Theotokos, we magnify you.“

An Orthodox Hymn to the Virgin Mary, known as the Axion Estin.

Finally, Orthodoxy agrees with the Catholic church that Christ is truly present in the Eucharist and that this and the other Holy Mysteries convey grace to those who receive them worthily.

A detailed article on the differences between the Catholic and Orthodox churches is given by the Orthodox Research Institute.

Orthodox Distinctives

Orthodox Distinctives

The church accepts the first seven ecumenical councils as having authority for dogmatic belief. In these Councils, the church believes that it was guided by the Holy Spirit to determine truth from falsehood.

The councils were:

- Nicea I (325) – Upheld the view that Christ was of one essence with the Father (thus repudiating Arianism) and adopted the first form of the Nicene creed.

- Constantinople I (381) – Revised the Nicene creed to the form now in use.

- Ephesus (431) – Affirmed Mary as Theotokos i.e. ‘Mother of God’, thus repudiating Nestorianism.

- Chalcedon (451) – Affirmed the doctrine of two natures in one person (the ‘hypostatic union’) in Christ and thus rejected the Monophysite doctrine of Eutyches.

- Constantinople II (553) – Affirmed the teachings of the previous councils.

- Constantinople III (680-1) – Repudiated the Monothelite heresy by stating the view that Christ has two wills – one human, the other divine.

- Nicea II (787) – Restored the veneration of icons following the iconclastic controversy.

Orthodoxy maintains a sense of the transcendence and immanence of God in a way quite unfamiliar to the west. The use of the term ‘Mysteries’ for what is known in the west as ‘Sacraments’ underscores this.

St. Gregory Palamas (1296 – 1359) drew a distinction between the following:

- The essence of God – That which is unknowable to Man.

- The energies of God in which God has revealed himself to us.

Simply put, Orthodoxy maintains that we can know God directly by his Uncreated Energies which are nothing more or less than his self communication to us, but we cannot know his nature which remains forever, completely and infinitely beyond our perception and comprehension.

Gregory championed a movement within Orthodoxy known as Hesychasm (From the Greek: Hesychia, ‘quietness’), a form of deep meditation. This became the official teaching of the Church in 1351. A common prayer used by hesychasts is known as the ‘Jesus Prayer’ :

“Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

This prayer is used by other traditions within Christianity, but it is popular in Orthodoxy, where it is seen as an important part of the faith, drawing the soul into deeper communion with God.

The writings of those in the Hesychast tradition were collected together in what became known as the Philokalia (Greek: ‘Love of good things’).

The aim of all Orthodox believers is to obtain Theosis, which might be defined as likness to, or union with God. Theosis is seen as the ultimate goal and the main purpose of human life. Theosis has three stages; the first being purification (katharsis) and the second illumination or the vision of God (theoria) and sainthood (theosis).

One of most distinctive features of Orthodoxy is its use of icons in worship. These are considered to be much more than merely pictorial representations of Christian figures. Icons act as a form of veneration or proskynesis, though as the church points out, the veneration is always given to the person represented by the icon, and not the icon itself. Basil of Caesarea worded it thus: The honour paid to the image passes to the prototype.

There was a serious dispute over the use of icons in the 8th and 9th centuries (known as the Iconclastic Controversy). It began in the reign of Emperor Leo III of Constantinople. Although the ecumenical council at Nicea in 787 restored the use of icons, the dispute was not finally settled until 843. To this day, this settlement is commemorated on the first Sunday in Lent in the Feast of Orthodoxy.

An Orthodox service (known as the ‘Divine Liturgy’) is mainly sung. There are several liturgies used, but ordinarily that used is the liturgy of St. John Chrysostom (347-407), Bishop of Constantinople. St. John was famed for his eloquence in preaching (‘Chrysostom’ is a Greek phrase meaning ‘Golden-mouthed’). The Divine Liturgy is discussed in the section The Mysteries.

Divine Liturgy in an Orthodox Church.

Feast Days

Feast Days

The most important feast day in Orthodoxy is Easter, also known as Pascha and the Feast of Feasts. In addition, there are twelve other feast days of importance:

- 6 January: Theophany – The Baptism of Jesus Christ by John the Baptist (Mark 1: 9-11).

- 2 February: The Presentation of Christ in the temple (Luke 2: 22-35).

- 25 March: The Annunciation (Luke 1: 26-38).

- Sunday before Pascha: Palm Sunday (Matthew 21: 1-11).

- Forty days after Pascha: The Ascension of Christ (Mark 16:19)

- Fifty days after Pascha: Pentecost (Acts 2).

- 6 August: The Transfiguration (Luke 9:28-36).

- 15 August: The Dormition (Falling asleep) of the Theotokos.

- 8 September: The Nativity of the Theotokos.

- 14 September: The elevation of the Holy Cross.

- 21 November: The presentation of the Theotokos.

- 25 December: The Nativity of Christ.

Note: The dates above are those used by those Orthodox Churches which have adopted the revised Julian Calendar (similar to, but not the same as, the Gregorian Calendar used in Western Christianity). These are known as New Calendarists (NC) in distinction from the Old Calendarists (OC), who maintain the use of the original Julian Calendar.

More Information:

More Information:

Here is a selected series of links that will give more information:

Antiochian Orthodox Church | Orthodox Church in America | Orthodox Photos | Orthodox Unity | St Aidans Church, Manchester

Wise words:

Wise words:

“…he who loves God cultivates pure prayer, driving out every passion that keeps him from it.”

St. Maximus the Confessor (580-662)